(An intro post on man/gap versus zone blocking can be found on my old blog here.)

Roughly 45% of your playcalls will be from the Ace Slot formation and 45% of your playcalls will be from the Ace Y-Trips formation, with the balance being the gimmicky stuff in Ace Slot Y Flex. The most heavily called bread and butter plays of the offense are the Inside Zone on Ace Slot and HB Stretch (Outside Zone) on Ace Y-Trips. Execution of these plays are the bedrock of the entire run game for us the same way it is for Alabama:

Roughly 45% of your playcalls will be from the Ace Slot formation and 45% of your playcalls will be from the Ace Y-Trips formation, with the balance being the gimmicky stuff in Ace Slot Y Flex. The most heavily called bread and butter plays of the offense are the Inside Zone on Ace Slot and HB Stretch (Outside Zone) on Ace Y-Trips. Execution of these plays are the bedrock of the entire run game for us the same way it is for Alabama:

They just use power and discipline and repetition over and over,” CBS commentator Gary Danielson said of Alabama. “It’s the equivalent of a back-shoulder throw on the bump-and-run. Nick says all the time that there’s no defense for that if it’s executed properly. The inside zone is the same thing. It’s the Lew Alcindor skyhook. Once he got the ball on his spot and then turned to shoot, you just hoped he missed.”

Danielson helped broadcast Alabama’s 32-28 victory over Georgia in the SEC Championship Game. Alabama ran for 350 yards, and Danielson came away saying there are more ways to control tempo.

“Tempo football doesn’t have to be hurry-up, trick-’em football,” he said. “Tempo football can be continue to mash them. …

“You can depend on these plays that they’re running over and over again. When you’re a Georgia player and you get to the sideline and you look at a coach, the coach looks back and says, ‘I got nothing for you. They’re knocking your ass off the ball.’ There is no tweak to stop that. You might have a tweak to stop the spread, but there is no tweak for the inside zone.”

The article linked above has the following quote from former Alabama Center William Vlachos:

Q. Is the inside zone a play, or a series of plays?

A. It’s a scheme. It’s a concept. You can have play-action off the inside zone. You can line up in the same exact formation and run the outside zone. The difference between inside zone and outside zone is just your aiming point and footwork. You’re still trying to accomplish the same thing. The backs end up going a little wider. As an offensive lineman, you’re aiming for the defender a little wider for leverage. What you’re trying to accomplish is the same thing. We run the zone out of several formations, but you can’t always tell if it’s inside zone or outside zone. You’ve got to read linemen and read running backs. It’s definitely not a play. There are many variations, formations. There’s a lot of stuff you can do out of it.This is what simplifies the running game for the NCAA/Madden player when we zone block everything; you get to read basically the same thing no matter which direction we are running the ball. Tim Layden has a nice bit on this from former Cleveland Browns OL coach Howard Mudd in Blood, Sweat and Chalk:

There was also a bonus. "Zone blocking is easier to teach," Mudd says. "There are fewer things that can go wrong because you're creating this mush, where guys are working with the guy next to him and there's just less space for things to go wrong. Now, with this, of course, you're going to lose some of the techniques that I grew up with - the angle blocking and pulling. But it's just easier. Over the years I've been in so many meetings where we said 'Ah, hell, let's just zone-block it.' And that's what we did. (p.129)The key is to not think of it as "Inside Zone" or "Outside Zone," but to instead just think of it as "Zone." Again, here's Vlachos:

Q. Does inside zone result in running inside and outside zone result in running wide?

A. No. A lot of times outside zone will cut back. The defense will over-pursue. To get the backside cut off, there are running lanes inside. There isn’t a hole that you have to hit, whether it’s inside zone or outside zone. On an inside zone play, a lineman has a certain angle, a certain fit relative to their helmet onto the defender, what kind of position they want their body in. On an outside zone play, it’s just a little wider.

So think of it as running a zone play to the strongside or zone play to the weakside. Whether you end up running the ball to the inside or outside depends on what happens during the play.

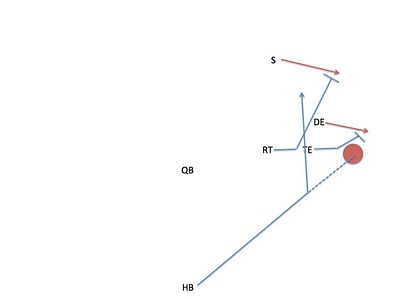

What you are looking for on a Zone Run

|

The offensive blockers, trying to keep everyone contained to the inside, see the guy run out of position to the outside and kick him further outside. That's what creates the hole to run through: overpursuers pushed outside and everybody else pushed inside - gap in between.

If more than one guy overpursues, they all get kicked out, and the back cuts back behind the last guy sealed off. The hole can open anywhere - it just depends on which defenders overpursue the play and get punished for mistakes.

The runner has to be able to watch for the hole and hit it when the blockers create it for him off the overpursuit. The read is important - Rich Rodriguez's spread option attack features an Outside Zone play:

After the handoff, the running back takes two steps past the quarterback, rolling downhill, aiming at the butt of the offensive tackle. The running back reads the first down defensive lineman to second down defensive lineman. The back has three options after his read of the down defensive linemen: bang, bend, or bounce.That means the HB is reading the play from the inside out. He looks at the inside-most cutback lane and takes it if it's open: bang the OG hole. If that's closed, he proceeds to the next hole and takes it if it's open: bend it off-tackle. Finally, if everyone on the offensive line has succeeded in containing the defenders inside, he can bounce the play to the outside. Bang, bend, or bounce.

This is essentially the same thing as the Colts' Stretch Play run out of the I formation instead of a single back formation. The blocking scheme tries to get double team combo blocks in place to set up a cutback lane somewhere along the line of scrimmage. The HB takes the ball and flows to the play side looking for an opportunity to cut it upfield through a lane behind one of these blocks. As Colts President Bill Polian describes Joseph Addai in the Colts' scheme, the stretch run requires patience on the part of the runner:

First of all, it depends upon the play that's being run. We have a series of plays that are called zone plays where we zone blocks where he has to hop. He's taught that. It's called a jump cut. He has to wait and be patient and wait for the hole to open up. At the professional level, especially with our offensive line, you don't just come off the ball and blast people back like you might do at the high school and college level. He's waiting for the hole to open up.

Bang: The Cutback

If the defense flows to the play direction and takes away everything in front of you, they are committing to take away the frontside and may be vulnerable to a cutback through the back side. Reading the play inside out, the first possible hole to hit is what we think of as a cutback by the runner. Consider the following two rushing plays:

In the first play, we have big separation at the handoff in the backside A gap (between the center and left guard). The assigned defender to that gap is the weakside linebacker.

As the ballcarrier flows to the right behind the line, the will turns down the line and takes a bad angle. Both the mike and will linebackers will end up piled up behind the mush of the offensive line, leaving a big hole in that backside A gap to run through.

In the second play, the defense is again flowing playside to take away what looks like the best hole in the frontside A gap:

The RT and RG have the two outside defenders under control and pushed to the outside, but the mike and will are rotating over to play the hole. The boxed sam linebacker is in a decent position to take away an outside run. All of this pursuit to the front of the play makes the backside B gap between the LT and LG that the will is vacating a good option.

Bend or Bounce? Reading Inside to Outside

If the defense plays you normally and actually maintains its gap integrity, the challenge is now to identify the first matchup your offensive linemen are winning. Here are eight zone plays:

On the first play, the initial read looks like the backside is taken away by the LDE and the best available hole is the frontside A gap. As the play develops, what happens is the center loses against the DT he's blocking, and the DT slips into that frontside A gap. At the last second, the best available hole becomes the backside A gap; not as good a hole as we had at first, but still a good gain since the tacklers get a bad angle and the back can get some yards off momentum.

In the second play, Louisville drops the strong safety down, but at the snap the linebackers and safety start dropping into zone coverage. With nobody to engage at the line of scrimmage, several blockers fire out and start looking for people to hit. The running lane is very obvious. Again, the cutback to the backside is taken away by the DE standing up, but there is no need to go there:

In the third example, we have the defense sending the middle linebacker on an inside blitz through the A gap, leaving the LDE isolated on the strong side. The RG comes off the combo block, leaving the RT on the LDE one on one.

The ballcarrier must now read the way the RT controls the defensive end. If the DE comes off the block inside, the correct read is to bounce it outside to keep the blocker between himself and the DE. If the DE comes off the block to the outside, we want to take a cutback lane inside the RT to keep him between the defender and the ball. The DE comes off to the outside, so the right read is to bend it back inside the tackle.

In the fourth run, we have inside zone run to the right, with the defense dropping into zone coverage rotating left away from the play direction. This sets them up well to take away the inside lanes and the backside cutback, but that means we have the advantage on the frontside:

The fifth and sixth examples are inside zone to the right with the defense sending inside pressure. Again, if they want to take away the inside running lanes, you continue to read forward and take the outside gap if that's what is available. Your blockers are trying to push someone out of position to the outside to widen a gap, but if all of the defenders want to stay inside, you have an opening out on the edge.

Finally, we have a pair of inside zone runs inside the five yard line trying to punch it in. The first of the two shows what happens when you make the wrong cut. Instead of bouncing to the outside against two defenders crashing the middle of the formation, the running back cuts it back right into them and gets stuffed:

The next play, we go back to the well and get the same kind of defense crashing the middle, but make the correct read and instead bounce it outside untouched for the score.