In the breakdown of how we use Curls, it was pointed out that you can stay with the Curls play against a defense with two high safeties if you trust your slot receiver to beat his man on the post. Against any Cover 2 shell, the slot post is a matchup throw that can get big yards, but it is risky and inconsistent. If the slot receiver doesn't win his matchup or the defense has good safety play that recognizes where the quarterback is going with the ball, there are few options left: both curls will be likely be covered close, and defenders will swarm quickly to the flat. It is generally better to check to a run or a pass play better suited to dealing with Cover 2 (zone or man).

A pass play we can check to against a two shell is Stick.

The best vertical or horizontal stretches use more than two receivers, with three or more receivers being used in various “zone flood” routes. If you caught the defense in the right look it was mathematically impossible for them to defend you: If you ran the three-level flood route against Cover 2, they had two guys (a corner and a safety) to defend three receivers; and if you caught a Cover 3/4-under defense with your all-curl concept, it was easy pick’ins

That's what we're talking about with Curls versus single high (Cover 3) or four across (Cover 4). The issue we had with Curls is that we don't have an answer to Cover 2.

Enter the triangle stretch. The insight behind the triangle is that the horizontal and the vertical stretch are combined to create a single straightforward read for the quarterback that provides answers no matter what the defense presents.

All of the major “new” (in relative terms) passing concepts are based on a triangle read. The weakness of the triangle stretch is that it’s typically only possible to only get a two-man horizontal or vertical stretch, whereas with a true “flood” you can place three (or more) receivers across the field on a given plane to truly defeat a defense. This limitation means that a triangle can be throttled by certain coverages that rotate to the triangle side.

But all this is counterbalanced by the triangle’s versatility: the route concept should result in a completion against almost any coverage, and, as will be shown further below, triangle stretches are also usually conducive to having a man-beating concept within them. And if the defense does roll to the triangle side, some kind of backside combination of passes or runs can be used to keep the defense honest. Indeed, the two most popular “triangle” stretches are the “snag” and the “stick” concepts, which are universally used as both ball-control zone beaters and blitz-man beaters. There’s a reason why they have quickly become maybe the most popular pass concepts in football given the simplicity of the throws and the ability to package these concepts with various backside combinations.

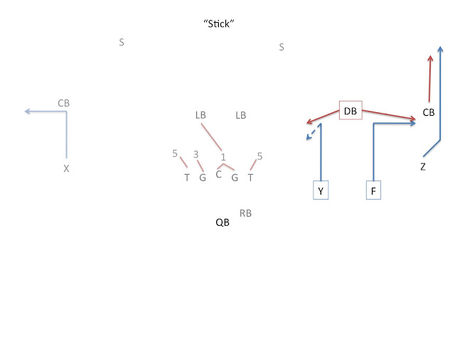

The play,

also commonly known as Y-Stick, can be run as a three step or

five step concept. We run it purely as a three step quick pass concept and in fact never send this in as the initial playcall. In the context of this offense, we use it only as an audible as a response to a two shell pre-snap look by the defense in Ace Y-Trips and are

not trying to set anything else up with it.

Going to this play as an audible is very easy because it is the default "quick pass" that both NCAA and Madden set as the "right stick up" play in the formation (Press X to instruct the game to audible, then push right analog stick up to get the quick pass defaulted to the formation - which is Stick for Ace Y-Trips).

Posting Up

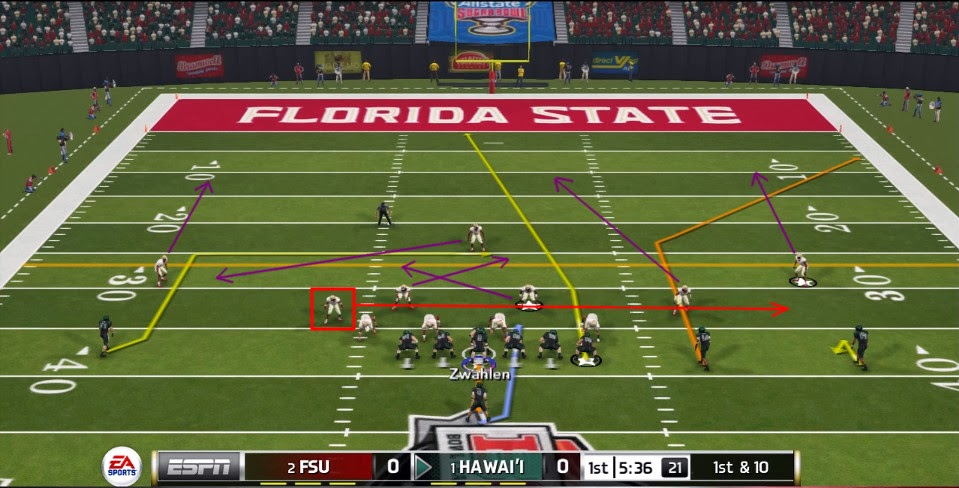

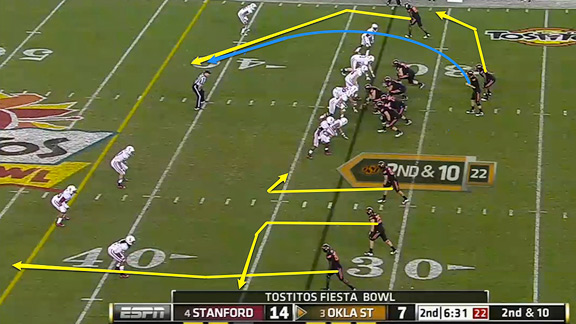

The way the play is designed to work is that you pair a vertical route and a quick out so there is one receiver deep and one receiver short - that's your vertical stretch via two guys along the sideline. Now add a third receiver also short but closer inside by the near hashmark - that's your horizontal stretch via two guys short to the same side of the field. Consider this picture of a Stick play from a

Grantland article by Chris Brown on Oklahoma State using it in its 2012 Fiesta Bowl win:

This is a mirror of our play diagram at the top: vertical run by the left WR, the slot runs a quick out, and the next guy in runs a short hitch. On the backside of the play, the lone WR runs a slant. The effect of the two stretches on the defense can be better seen in this diagram from

Dawgs by Nature:

For the most part in both Madden and NCAA, the underneath defender labeled DB in that diagram almost always opts to cover the flat because he has help inside but is the last man who can stop the route breaking to the outside. That leaves the Y receiver to be covered by a linebacker who is usually out of position.

The primary receiver in the playart in Madden and NCAA is correctly identified as the TE, who is playing the part of the Y receiver. Tight Ends in the past were hard to find because so many athletes with the necessary body types

would go play basketball as power forwards.

In the Stick play, that's exactly what we want our

Power Forward to do: post up and get the ball in the lane. Watch the Y receiver in these Stick plays from a Saints-Patriots preseason game. They run down the field, stop and turn and put their hands up for the ball. In particular, watch the second play where

Brian Hoyer throws the out to Shane Vereen instead of the stick to Alex Silvestro: the TE still brings his hands up and is ready to catch the ball

whether it is coming or not.

Of course, the Saints also run the stick concept:

Stealing Yards

The read we use is the same as on the Live to Win blog for the Stick play out of a 3x1 set:

Our Progression: (With Access CLOSED)

Z: is a pre-snap read only. Z is out of the equation unless we see two things: Man Coverage or Cover 2 with a big window.

Y to H: The rule is simple; the ball automatically goes to the Y unless color covers the route. Color = H on the speed out.

The goal is to out-leverage the invert or force defender with a horizontal read and make him wrong.

The reason Chris Brown says the three man stick concept to the strong side "is good against almost all zone coverages" is because the TE will post up in front of the linebacker. As long as the man over the slot runs with him to the flat (and he always will), the TE will be up against a linebacker who will do one of two things.

If the linebacker is in zone coverage, he will start flowing or backpedaling into his zone once he diagnoses "Pass." That means he is already moving away from the TE, and "

off coverage isn't going to do much against a well run stick." Like our Curls routes getting separation by

stopping suddenly in front of zone cover men backing away from them, the TE will settle into the seam between the LB in the inside zone and the defensive back being dragged outside by the slot receiver's quick out: the out is designed to widen the seam.

If the linebacker is in man coverage, he will run to the TE once he diagnoses "Pass." That can be bad because either the TE will get blown up and possibly drop the ball or the LB might even step in front and intercept the pass if he's close enough. That's why the Stick play has the TE's route shown as an option route that most times will look like a quick stopping comeback route, but leaves an option to also turn it into a quick out:

Now, as you can see, the Y-receiver, who for Texas Tech this year will be Jace Amaro, is the second read in the quarterback's progression but he's usually the player that will get the ball. This is due to the fact that there is a hole in the zone defense created by the running backs route to the flats. The safety, nickel or strongside linebacker will, usually, have to choose to cover either the tailback in the flats or the Y-receiver, and, traditionally, will pick the flats. That leaves a hole for the Y to shuffle outside and catch the ball while facing the quarterback. Against man coverage, the Y receiver will run the stick again, but he'll usually cut in a much more vicious fashion to get a good release of the defensive back, pivot inside and wait for the ball.

This is considered a high-percentage play because it's usually an easy throw that will move the ball forward no matter what defense you might be facing.

The option to also run a quick out makes it possible to throw the stick against just about everything, but that doesn't make it a good idea. Again, simple throws to very open receivers is the best way to compensate for a low talent roster. Good talent makes other things possible, but better players can still do the same things worse players are able to do successfully. Throwing the TE against man coverage is relying on the TE to make a good read and take the option route to cut outside and then beat his man. A couple of things can go wrong here - the TE might not read the defense right and make the quick out, the TE might not be a good enough route runner to get open, or the LB could be a superstar or lined up in a great position that closes the distance too fast and he makes a great play on the ball.

The Backside Man Beater

Let's go back to the first picture we had of Oklahoma State running Y-Stick in the 2012 Fiesta Bowl.

Brown points out that Justin Blackmon is running a standard man beater slant concept on the backside:

To Blackmon’s side, the Cowboys ran a simple “slant/flat” combination, where Blackmon runs a slant while the runner runs a route to the sideline to control the flat defenders. This route is good against some zone coverages as well, but it’s primarily here for man-to-man: If Stanford tries to single out Blackmon, that’s where Weeden is going with the ball, and that was what they did.

While we lack the accompanying flat route from the back, we also have a slant on the backside, which is a great man beater. This goes with our philosophy of

packaging coverage beaters to ensure the quarterback has a good place to go with the ball no matter what the defense is doing.

At the snap of the ball, we stare at the TE stick and check to see what the LB is doing. If the LB jumps the route, that tells us immediately we are facing man coverage. Instantly, we should look at the slant. Since we are only ever checking into this play against a two high look with corners rolled up on the line in our wide receivers' faces, the LB telegraphing man means we can expect to see our WR getting press coverage on the outside.

This is a good matchup because the cornerback playing press coverage is counting on the blitz to get to the quarterback while his bump at the line throws off any timing the offense is counting on. The problem is that we aren't trying to time this particular route, and

it is already the kind of route you would throw hot against a blitz. All we do in this situation is wait for the receiver to come off the press (he will eventually), and immediately break to the inside after getting a step past the cornerback. It's when he makes his break and the corner doesn't know which way the WR is going to run that we make the throw. The receiver will plant and drive to the inside, running to where the quarterback is delivering the ball. Against man coverage behind a blitz, this is generally good for 10-12 yards and almost always a wide open throw.

Here is Sir Charles on what happens when you hit the TE on the stick enough times against zone coverage:

This is what makes the Curls/Stick/Dive combination so nasty - each component opens up the other parts of the scheme. Pretty soon you start to see the defense playing a ton of 2 Man Under trying to shut the TE stick down, but then you can start to run the ball or throw the slant on the backside. If they start calling single high man coverages to stop the slant or try to drop the SS down into the box to play a Cover 3 scheme, that plays into our hands: we never check to Stick to begin with and

take the Curls for first downs.